RICH AND STRANGE – 1931 – British International Pictures – ★★

B&W – 83 minutes – 1.33:1 aspect ratio

Directed by Alfred Hitchcock

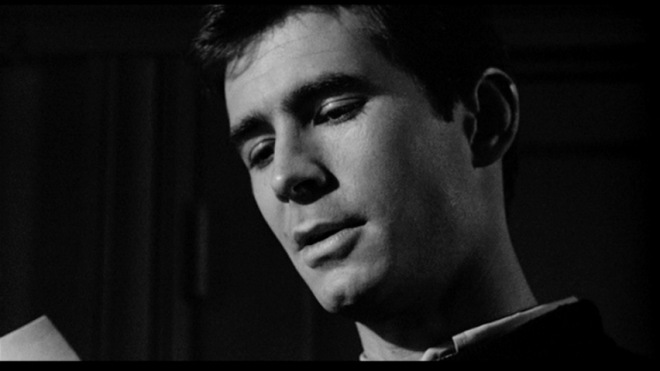

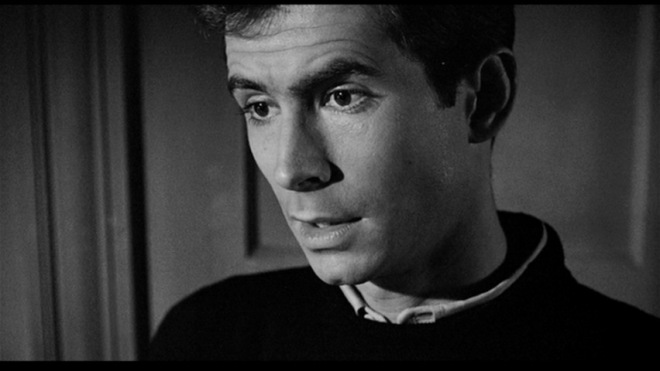

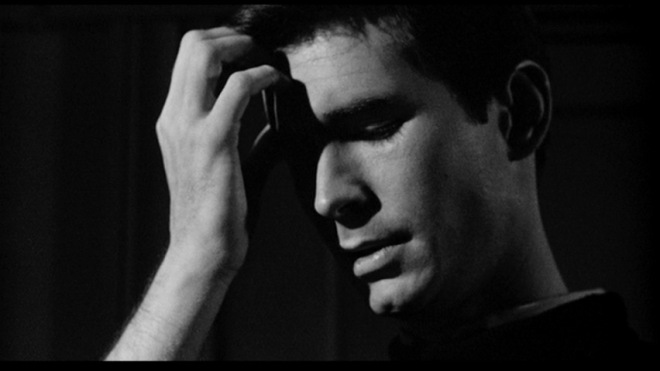

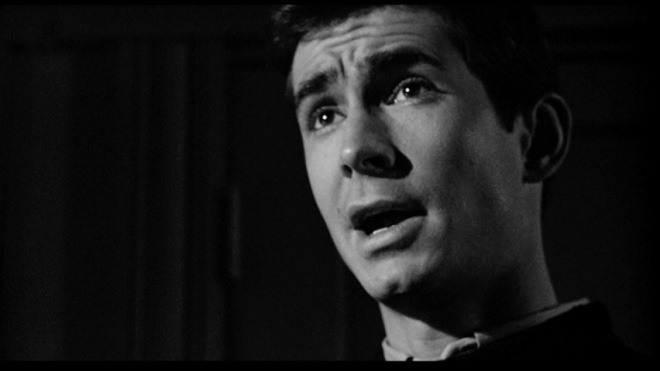

Principal cast: Henry Kendall (Fred Hill), Joan Barry (Emily Hill), Percy Marmont (Commander Gordon), Betty Amann (The Princess), Elsie Randolph (The Old Maid).

Screenplay by Alfred Hitchcock, adaptation by Alma Reville and Val Valentine, based on the novel by Dale Collins

Cinematography by Jack Cox

Edited by Winifred Cooper and Rene Marrison

Music by Adolph Hallis

A Hitchcock comedy: This might not be a straight comedy, but it is as close as Hitchcock ever came in his British period. Hitchcock creates a funny opening sequence that requires no sound to be effective. Fred Hill (Henry Kendall) is seen at the end of the working day, surrounded by coworkers.

We observe throngs of people leaving the office.

One man after another goes outside and opens his umbrella. Fred fumbles with his, which turns out to be broken. Off into the rain he goes.

Next we see him on the underground platform, pressed in on all sides.

Finally aboard the subway, he loses his balance and inadvertently plucks a feather from a woman’s hat, which he sheepishly returns to her.

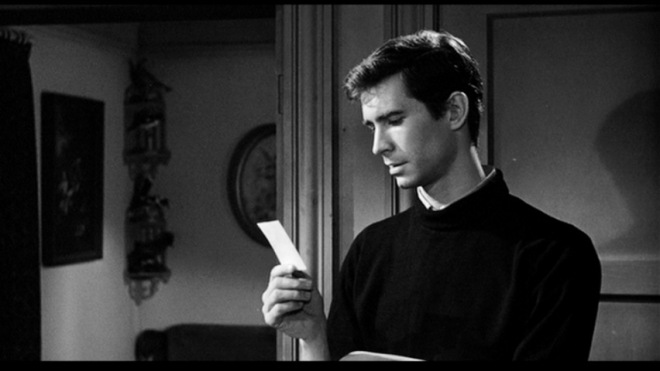

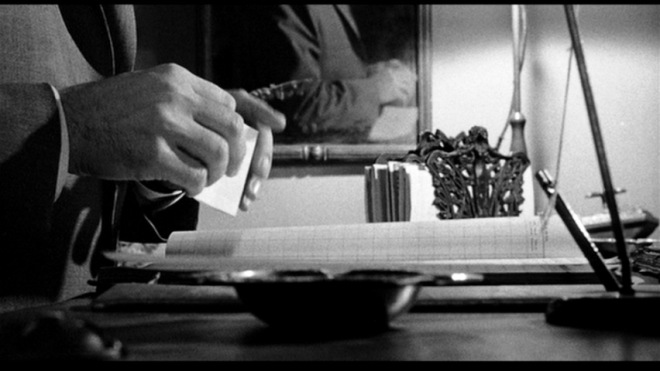

Glancing at his paper he sees the following advertisement.

This introduction is none-too-subtle, but it sets up the premise well enough. When Fred gets home, he tells his wife Emily (Joan Barry) that he is fed up with life. It is excitement he craves. This dialogue is the cue for a well-timed letter informing Fred that he has just inherited some money from his uncle. So off Fred and Emily go, traveling around the world.

A talkie with titles: Considering that Hitchcock had already made several films with sound at this point, including some that made very innovative use of the new film medium, it is curious that he chose to make a film in which sound is almost superfluous. This film (particularly the latter two-thirds) is full of title cards, just as one would see in a silent film.

I have read at least one source that alleges the title cards were necessary because much of the film was shot on location. I’m not sure I buy that theory because there are dialogue scenes that could have included exposition left to the title cards. Clearly this was a choice. One advantage of the location shooting is getting nice shots of the local landmarks.

Even many of the jokes are visual in nature, and would have worked in a silent film, including one of the best, when a drunk Fred tries to set his watch to an elevator floor indicator.

Another nice visual joke comes later on board the ocean liner, when a seasick Fred looks at a menu and the words seem to be leaping off the page.

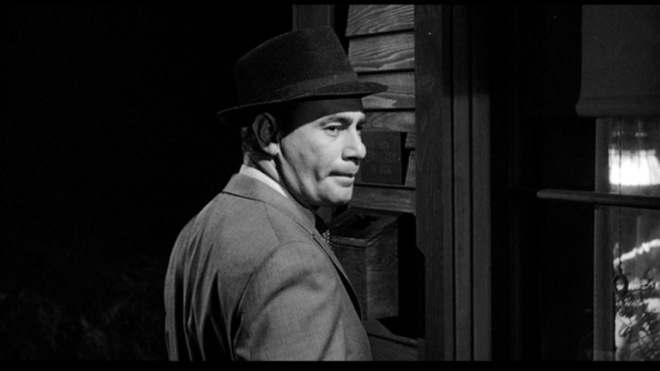

Many of the shipboard scenes are rather trite. While Fred is seasick, Emily befriends (and begins to fall for) Commander Gordon (Percy Marmont) whose company is sought by many women, including a spinsterish lady played by Elsie Randolph.

When Fred recovers, he begins to fall for a woman who is referred to as “The Princess” (Betty Amann).

The passengers disembark in Singapore. Fred soon discovers that the Princess is no royalty at all, but a swindler, who promptly absconds with the bulk of his money. Emily was planning to leave with Gordon, but she feels sorry for Fred and so stays with him. The two have just enough money for cheap steamer passage home. On the return voyage, the ship begins to sink.

The two are rescued (along with a black cat) by a Chinese junk. A rather tasteless joke ensues, in which the couple are seen ravenously eating bowls of food offered by the Chinese, after which they see the cat’s skin being nailed to the ship (the implication being that they have just eaten the cat!) At this point they fling their heads over the rail, presumably to throw up.

And the movie ends where it began, in their London flat, only now they appreciate their day-to-day life.

Missing footage? Every print of this film I have come across has an 83-minute running time. And yet I have seen at least 5 different reputable sources that cite a 92-minute version, when the film was first released in Britain. What happened to this missing 9 minutes? Is there a print of the original version out there somewhere? It would be interesting to see what it contained. Perhaps Hitchcock’s cameo, which does not exist in the 83-minute version? He discussed it with Peter Bogdanovich as if it had been shot. Or perhaps this scene, that Hitch recalls from memory, in discussion with Truffaut:

Hitchcock: …there was a scene in which the young man was swimming with a girl, and she stands with her legs astride, saying to him “I bet you can’t swim between my legs.” I shot it in a tank. The boy dives, and when he’s about to pass between her legs, she suddenly locks his head between her legs, and you see the bubbles rising from his mouth. Finally, she releases him, and as he comes up, gasping for air, he sputters out, “You almost killed me that time,” and she answers, “Wouldn’t that have been a beautiful death?” I don’t think we could show that today because of censorship.

Truffaut: I’ve seen two different prints of that picture, but neither one showed that scene.

If this scene is part of the missing 9 minutes, then it would seem like it was already missing in the early 60’s, based on this interview clip.

Performance: Hitchcock blamed this movie’s box office failure on his casting choices in the leading roles. As fond as Hitchcock clearly was of the screenplay, I’m not sure any actors could have saved it. That being said, this movie was designed to be carried by the starring couple, and the chosen actors do very little to engage or inspire. Henry Kendall and Joan Barry have absolutely no chemistry, with each other or the love interests they develop along the way. Betty Amann as “The Princess” is just as vapid and lifeless as Joan Barry. Anyone who would fall for her deserves what he gets. Percy Marmont is at least passable as Commander Gordon. The only really pleasurable performance in the entire film is that of Elsie Gordon as the old maid. I imagine her role as written was pure caricature; she manages to make it both funny and human. The film could have used more such performances.

Source material: There is more than one book that claims Dale Collins either wrote the novel Rich and Strange in conjunction with the Hitchcocks, or that he wrote it specifically for Alfred Hitchcock as a sort of treatment. If that is true, I have found no evidence to support it. On the contrary, in the Library of Australia I found a review of Collins’ novel from the December 12th, 1930 Sydney Morning Herald, almost a year to the day prior to the movie’s release on December 10th, 1931. It seems highly unlikely that the book was written with Hitchcock in mind.

I have been unable to procure a copy of the book to read, so I can’t provide my customary comparison between the book and film. Instead, I will add the complete newspaper review here, which provides a neat summary, and shows that book reviews haven’t changed much in the better part of a century:

In their suburban home Emily is happy but Fred is discontented. He is a London clerk, and his humdrum life weighs him down. The postman calls, and a letter arrives announcing that they have been left a legacy of £3000, which is to be spent having “a good time.” They go travelling. On a steamer bound for the East Fred becomes enamoured of a princess with those “tawny” eyes that are so often found in novels. His wife falls in love with a passenger, Gordon. By the time they near Singapore Fred has determined to run off with the princess and Emily with Gordon. On arrival in port the princess turns out to be an adventuress and disappears with £1000 of Fred’s money; Emily cannot face carrying her affair with Gordon to conclusion. They sail on together, therefore, in the steamer, which comes to disaster, and the two, imprisoned in their cabin, deserted by all the others, are rescued by Chinese on a Junk, which takes them to Japan-nearly dead, and, when safe ashore, ready enough to resume suburban life in England.

It is a somewhat ordinary story, with little to raise it to the heights. The author introduces himself among the characters:

Recurring players: Joan Barry had earlier provided the live-on-set English voice dubbing for Anny Ondra in Blackmail. Percy Marmont would later appear in both Secret Agent (as Caypor) and Young and Innocent (as Col. Burgoyne). Elsie Randolph would appear 41 years later as Gladys in Frenzy, the longest gap between appearances in Hitchcock films. And Hannah Jones (the uncredited Mrs. Porter) had earlier appeared in Downhill, Champagne, Blackmail, and Murder!

Where’s Hitch? There is no surviving Hitchcock cameo in this film, although Hitchcock did have a clever one planned, and even told Peter Bogdanovich that it was filmed, although it does not exist in any surviving print. In the Dale Collins novel, there is a scene in which the protagonist couple enter a bar and encounter the author of the very novel they are in, who tells them their story is too outrageous. Hitchcock planned a variation on this, where the leads would meet him as director Alfred Hitchcock. After hearing their tale, he would reply “No, I don’t think it will make a movie.” This missing (or possibly never made) cameo is one of the many frustrating aspects surrounding this movie.

What Hitch said: Hitchcock seemed to be fond of this picture, saying “It had lots of ideas…I liked the picture; it should have been more successful.” He also had an opinion about why the movie was a box office flop: “My mistake with Rich and Strange was my failure to make sure that the two leading players would be attractive to the critics and audience alike. With a story that good, I should have not allowed indifferent casting.”

Definitive edition: Kino Lorber released a blu-ray edition of Rich and Strange in 2022 as part of their fantastic KL Studio Classics series. The print is the BFI’s 4K restoration, and the movie has arguably never looked and sounded this good. Included along with the film are an introduction by Noel Simsolo, an adequate commentary track by Troy Howarth, an audio excerpt from the Hitchcock/Truffaut interviews pertaining to this movie, and the trailer for this and several other Hitchcock films that have been released by Kino Lorber.