When one thinks of Alfred Hitchcock one does not think of sequels. And while he never directed any sequels himself, his 1960 release Psycho has generated quite a legacy on film, television and in print. There are three feature-length sequels, all with Anthony Perkins reprising his role as Norman Bates. There are two television shows, one that never made it past the pilot episode, and one that has just concluded its first successful season. Robert Bloch also wrote two sequels to his original novel, something he arguably would not have done had the movie not been such a success. There is an excellent non-fiction book by Stephen Rebello about the making of the original film. There is a movie based loosely on Rebello’s book. And there is also a remake directed by Gus Van Sant. (I should note that Alfred Hitchcock had nothing to do with any of these projects; they all were released after his death in 1980).

When one thinks of Alfred Hitchcock one does not think of sequels. And while he never directed any sequels himself, his 1960 release Psycho has generated quite a legacy on film, television and in print. There are three feature-length sequels, all with Anthony Perkins reprising his role as Norman Bates. There are two television shows, one that never made it past the pilot episode, and one that has just concluded its first successful season. Robert Bloch also wrote two sequels to his original novel, something he arguably would not have done had the movie not been such a success. There is an excellent non-fiction book by Stephen Rebello about the making of the original film. There is a movie based loosely on Rebello’s book. And there is also a remake directed by Gus Van Sant. (I should note that Alfred Hitchcock had nothing to do with any of these projects; they all were released after his death in 1980).

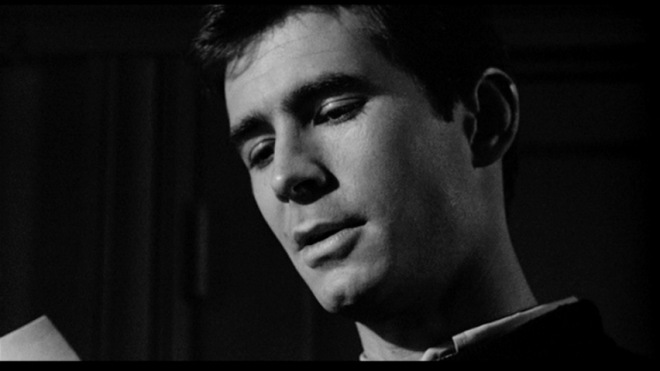

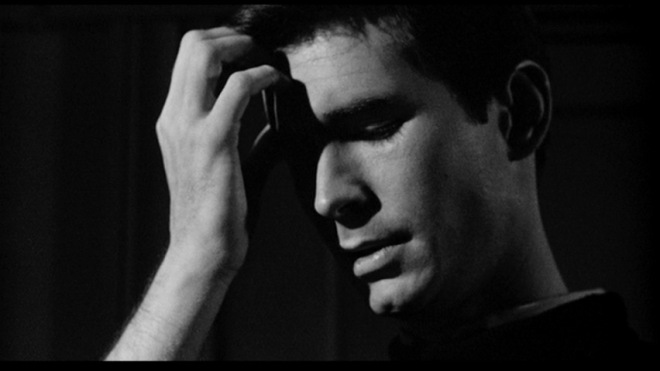

Psycho II (1983) – Universal – Rating: ★★1/2

Color – 113 minutes – 1.85:1 aspect ratio

Directed by Richard Franklin

Principal cast: Anthony Perkins (Norman Bates), Vera Miles (Lila Loomis), Meg Tilly (Mary Samuels), Robert Loggia (Dr. Bill Raymond), Dennis Franz (Warren Toomey).

Written by Tom Holland

Music by Jerry Goldsmith

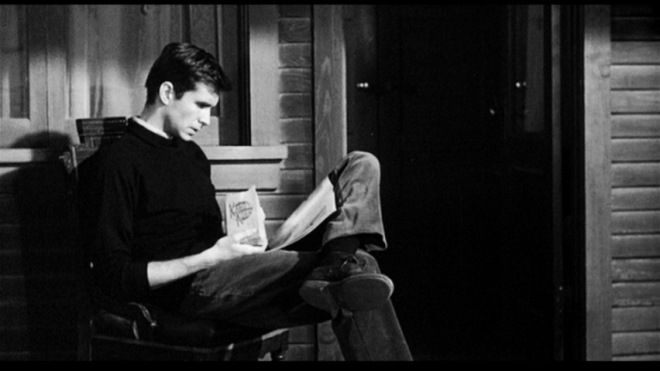

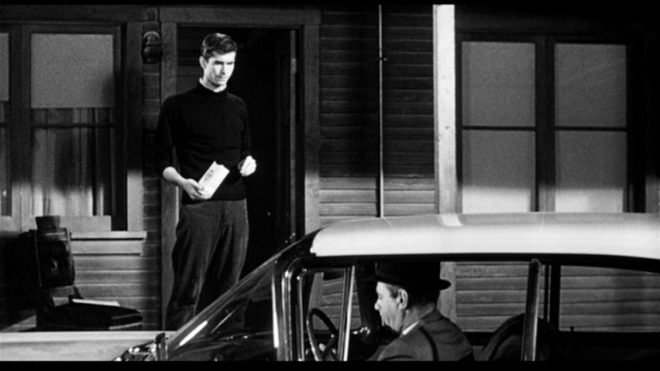

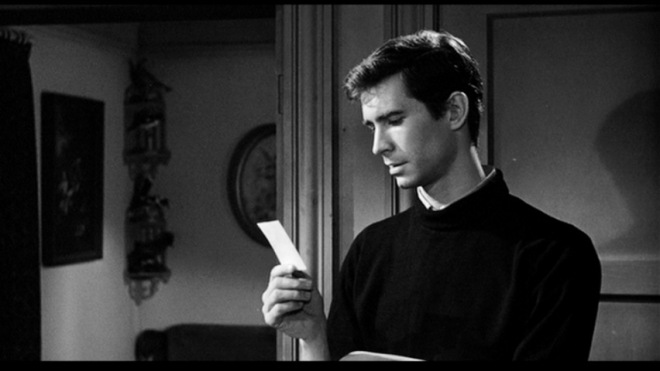

First off, let’s acknowledge that Psycho did not need a sequel. But the horror genre was experiencing a massive popularity burst in the early 80’s, thanks in large part to movies like Halloween and Friday the 13th. And Universal Pictures owned the rights to the original movie, which meant they could use its characters, or even steal scenes from it. They also still had the Psycho house standing on their backlot. (The motel building had been torn down, and had to be rebuilt.) And the most important piece of the puzzle: Anthony Perkins, who somewhat reluctantly agreed to reprise his role as Norman Bates.

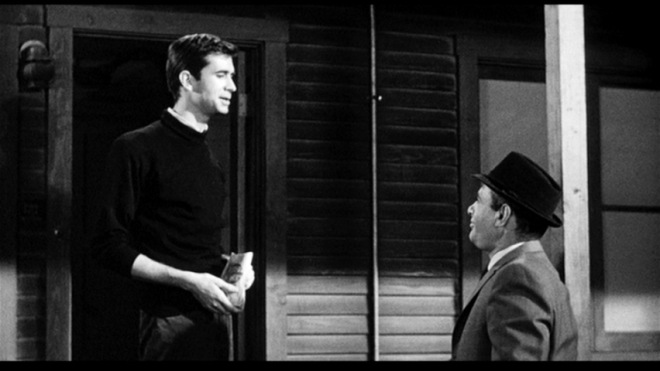

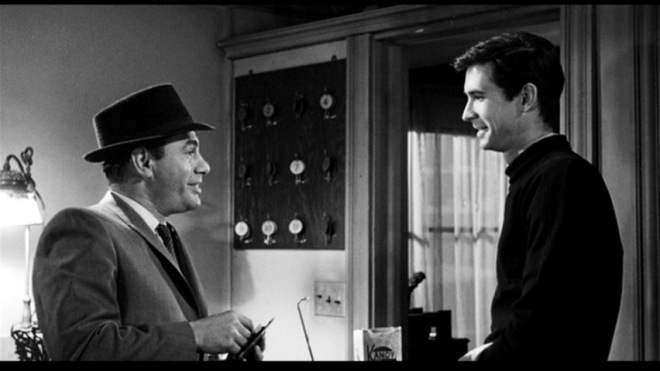

This movie is in trouble from the very first moment. It begins with the shower scene from the original Psycho, but in edited form! How can you edit one of the most iconic scenes in movie history? Either let it play out, or don’t use it at all. The set-up for the film is actually quite good, and the tagline on the movie poster sums it up as well as anybody could: “It’s 22 years later, and Norman Bates is coming home.” Norman is released from the mental facility where he has spent over two decades, and returns to his childhood home to find the Bates Motel being run by an obnoxious sleazebag played by Dennis Franz (this is before Franz made the switch from obnoxious sleazebags to endearing sleazebags.) Within five seconds of meeting Franz’s character we know he is going to die, and this points to the movie’s biggest problem; there is just no subtlety to be found, either in plot or dialogue.

Anthony Perkins and Vera Miles are both very believable in the roles they had initiated over 20 years earlier. It’s quite plausible that Lila Loomis would have married Sam after the death of Marion. It’s also believable that Lila would hate Norman Bates, and do anything to get him locked up for good. It is a bit of a stretch, however, to believe that she would use her daughter as a pawn in a potentially deadly game. Robert Loggia is very solid in the role of Robert Loggia. (That is not meant as a slight; he is a good character actor, who helps keep this movie from going completely off the rails.) Meg Tilly is, well, annoying at best. Rumor has it that Anthony Perkins did not get along with her, and asked for her to be replaced at some point during filming. Honestly though, you could put any other actress in that role and it would not have been enough to save the rest of the movie.

Jerry Goldsmith wrote a beautiful score; too bad it sounds like the score of an entirely different film. Of course, what does one do when scoring a sequel, when the original film has one of the most iconic scores in movie history? He could either follow in Bernard Herrmann’s footsteps, or go another direction entirely. Goldsmith chose the latter, and it just doesn’t quite suit the material.

So, people are stabbed to death, Norman questions his sanity, and let’s not forget about the surpsise ending. There is an absolutely ludicrous plot twist that seems to undermine the logic of the original movie. I can’t really fault the director Richard Franklin, who was a student of Hitchcock, no less, but a stronger script may have helped this be something more than what it is. The movie is not a total loss; there are some fine moments, and Anthony Perkins is great.

Definitive edition: Shout Factory released a blu ray edition in 2013. First of all, the sound and picture quality are very good. Included with the film are an electronic press kit, which has audio and video issues and repeats itself. For all that, it does have some good interview clips. Also included is an audio commentary with screenwriter Tom Holland, and audio promotional clips, as well as a photo gallery and trailers.

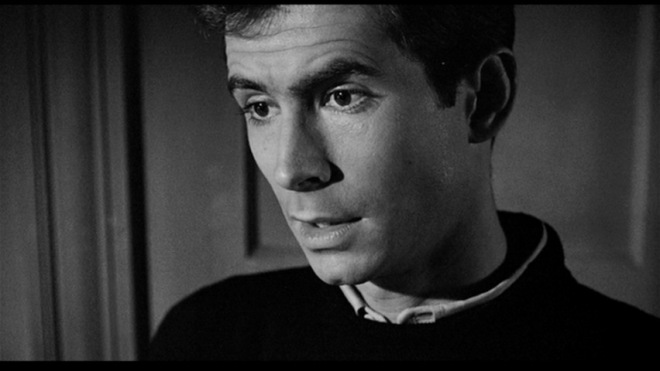

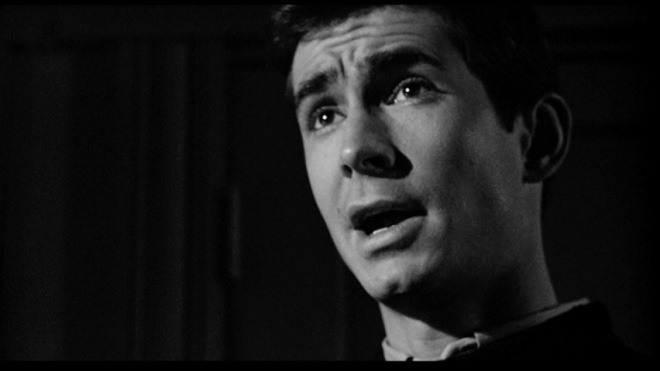

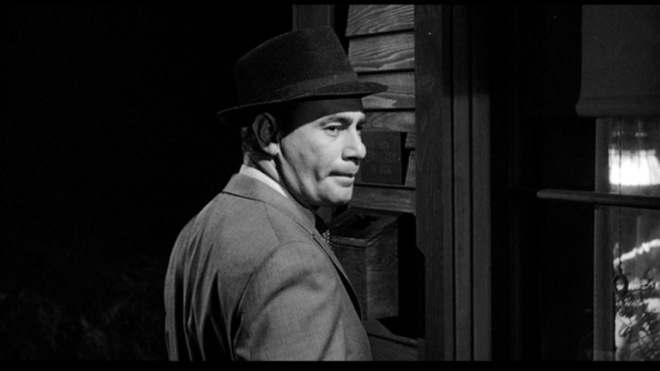

PSYCHO III (1986) – Universal – Rating: ★★★

Color – 92 minutes – 1.85:1 aspect ratio

Directed by Anthony Perkins

Principal cast: Anthony Perkins (Norman Bates), Diana Scarwid (Maureen Coyle), Jeff Fahey (Duane Duke), Roberta Maxwell (Tracy Venable), Hugh Gillin (Sheriff John Hunt).

Written by Charles Edward Pogue

Music by Carter Burwell

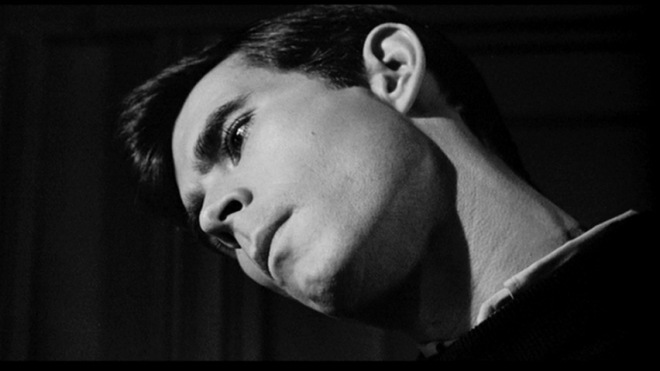

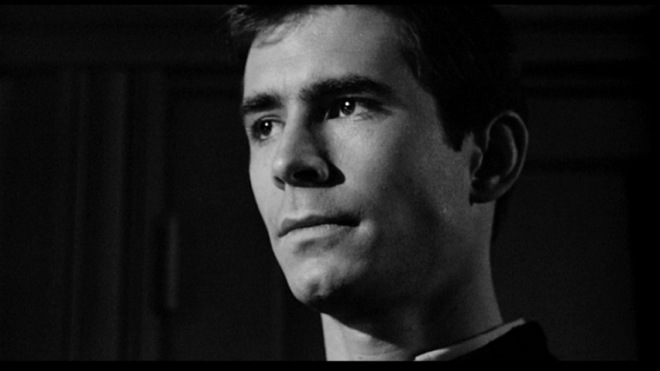

The third chapter in the Psycho series is somewhat better than its predecessor, but is still miles away from being a truly good film. Norman is back to his crazy ways, having installed Mother 2.0 in the bed where he kept the first model. Norman has a love interest again, this time a nun who has been kicked out of her convent. She caused a mother superior to fall to her death, in a scene that deliberately (and quite effectively) evokes Hitchcock’s Vertigo. She ends up at the Bates Motel, along with Jeff Fahey’s character Duane, a drifter looking to make a score, and make it with every woman who crosses his path. Hugh Gillin reprises his role from the last installment as Sheriff Hunt, a man who sympathizes with Norman Bates and wishes everyone would just leave him alone.

So, this being a Psycho movie, you can be assured that people will die violent deaths, and Norman will wage his mental battle with Mother. And that is what really drives this movie, and makes it worth watching. Anthony Perkins still makes Norman Bates a sympathetic character. We watch him perform acts of evil, and yet still root for him to somehow overcome in this struggle with his dead mother, who is the real source of evil.

Anthony Perkins directed this movie, and did an admirable job, considering it was the first (and only) time he sat in the director’s chair in his career. He overcame his initial nervousness about directing, and won over everyone on the set. Several cast and crew members remarked that Perkins was a pleasure to work with as a director.

Psycho III throws in a plot twist at the end, regarding Norman’s family tree, that seemingly attempts to untwist the twist at the end of Psycho II. Once again, ludicrous! But if you’re watching this movie, you’re not doing so for plot points. You’re doing it because you just can’t get enough Norman Bates.

This movie also features one of Carter Burwell’s early film scores, and it really plays well. Burwell made a modern (for the time) score, eschewing strings altogether, and that turned out to be a great decision.

Definitive edition: Once again, Shout Factory’s 2013 blu ray release has good sound and picture quality, and a handful of extra features. Included is a commentary track with the screenwriter, and several interesting featurettes, as well as a photo gallery and trailers.

Psycho IV: The Beginning (1990)- Universal – Rating: ★★1/2

Color – 96 minutes – 1.78:1 aspect ratio

Directed by Mick Garris

Principal cast: Anthony Perkins (Norman Bates), Henry Thomas (Young Norman Bates), Olivia Hussey (Norma Bates), C.C.H. Pounder (Fran Ambrose).

Written by Joseph Stefano

Music by Graeme Revell

When a horror movie franchise reaches part 4, you know its time for the inevitable flashback motif to show up, if it hasn’t already. And so a good part of this film is the older Norman Bates recounting his teenage years. For the first time we see Norma Bates in the flesh, and we see how Norman became who he became. This movie was written by Joseph Stefano, who wrote the screenplay for Hitchcock’s original 1960 Psycho. Stefano does a pretty decent job; I would say the screenplay is definitely better than the last two movies in the series. Some have said that it is highly improbable Norman Bates would have been released from the insane asylum a second time, and that is certainly true. But Joseph Stefano wrote this as a follow-up to his original movie, more-or-less ignoring the existence of Parts II and III altogether. If you take that into consideration, the plot of this film makes a little more sense, although its probably a little too late to introduce sense into this movie franchise, considering how senseless the last two screenplays were.

Anthony Perkins initially expressed interest in directing this installment as well, but Universal nixed that idea, based on the poor box office of the Perkins-directed part III. As it turns out, the potential box office of part IV was not a factor, because it was never released in theaters, but instead went straight to video, premiering exclusively on the Showtime cable TV network in 1990.

The set-up here is pretty good. Norman Bates calls in to a radio talk show hosted by Fran Ambrose. Fran is played quite convincingly by C.C.H. Pounder. Norman admits that he has killed, and says he is going to kill again. While on the phone with Fran, Norman talks about his childhood, and we get to see several flashback sequences showing Norman in his teenage years. The young Norman is played well by Henry Thomas of ET fame. He does not try to copy Anthony Perkins’ mannerisms in any way, which was a good decision. And young Norman’s mother is played in creepily good fashion by Olivia Hussey.

Norman’s present-day situation, and the reason that he feels he may have to kill again, is both surprising and disturbing. And the film’s resolution seems to imply that the Bates family saga has finally come to a conclusion. This movie is better than the cable TV movie-of-the-week status to which it was relegated. It is interesting to observe the ease with which Anthony Perkins now slips in the skin of Norman Bates. And while the quality of the movies definitely declined, Perkins’ performance is a marvel; he stayed true to the character, and made his atrocities believable from first to last. (When Psycho IV was being filmed, Anthony Perkins had already been diagnosed as HIV positive, and was receiving treatment during filming. This was one of the last projects he completed before his death.)

Definitive edition: Shout Factory released this on blu ray in 2013, with a nice looking print of the film. The behind the scenes featurettes on this one are not very engaging. One time is enough, if that. The commentary track however, with director Mick Garris, and actors Henry Thomas and Olivia Hussey, is quite engaging.